Tuesday, September 2. 2025

The very first Chuck Berry LP album

What was the very first 33rpm LP album containing Chuck Berry?

Now write down your answer, then scroll down ...

If your answer was "After School Session", you know your Berry quite well. Indeed, this album from May 1957 was the very first 33rpm LP containing just Chuck Berry recordings. Released by CHESS under the catalog number LP-1426 this album contains most of Berry's first seven CHESS singles (except four tracks) plus two previously unissued instrumentals.

However, this was not the first 33rpm LP album containing Chuck Berry.

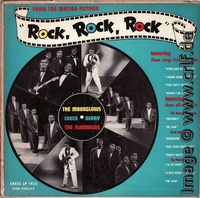

If your answer was the CHESS sampler "Rock Rock Rock", you know your Berry very well. Yes, as the number LP-1425 indicates, this album was released before LP-1426 "After School Session" und it was the very first 12" LP album published under the CHESS label name.

In case you wonder why the first CHESS album was already numbered at 1425, you'll find the answer in Nadine Cohodas's great book "Spinning Blues into Gold": The Chess brothers' first home in the U.S. after immigrating from Poland was at 1425 South Karlov Avenue, Chicago. The number 1425 was also used for the first 45rpm single issued under the CHESS label name: Bless You b/w My foolish heart by the Gene Ammons Sextet in June 1950.

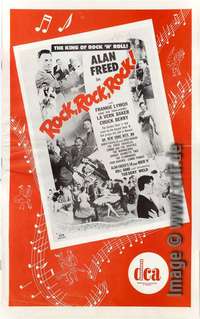

"Rock Rock Rock" is the title of a music film starring Alan Freed. The film was released December 7th, 1956 to the movie theaters in the U.S. (though some sources say December, 5th). On the very first days, Alan Freed, Chuck Berry, and Connie Francis were on stage in a couple of New York theaters for a few minutes each to promote the film. Record labels such as CHESS, whose artists performed in the film, were allowed to promote their records at the cinemas showing the movie. CHESS took this opportunity to concurrently (i.e. December 1957) create an album of same title which looks like a soundtrack album but instead contained only those artists under contract by CHESS: the Moonglows, the Flamingoes, and Berry.

CHESS LP-1425 contains the four songs performed by CHESS artists in the movie:

- "I Knew From The Start" - The Moonglows

- "Would I Be Crying" - The Flamingos

- "You Can't Catch Me" - Chuck Berry

- "Over And Over Again" - The Moonglows

- "Maybellene" - Chuck Berry

- "Sincerely" - The Moonglows

- "Thirty Days" - Chuck Berry

- "The Vow" - The Flamingos

- "Roll Over Beethoven" - Chuck Berry

- "I'll Be Home" - The Flamingos

- "See Saw" - The Moonglows

- "A Kiss From Your Lips" - The Flamingos

However, this was not the first 33rpm LP album containing Chuck Berry.

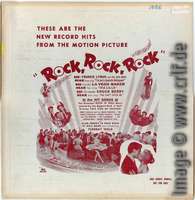

The very first Chuck Berry album has no title and no catalog number. All it says is "These are the new record hits from the motion picture Rock, Rock, Rock". And here's its story:

The movie "Rock, Rock, Rock" was a project by well-known New York disk jockey Alan Freed. And he wanted to get as much money from it as he could. First he owned 10 per cent of the film outright. Second he played a leading role. And third he planned to cash on the music presented therein. So Freed talked the executives of the six record companies whose artists perform their songs in the movie to pass over the publishing rights for the songs to his own Snappner Music Inc. company. He succeeded with 15 of the 20 songs.

Next, in return for allowing the record companies to display their disks in all theaters where the film plays, Freed got himself permission to use the songs on a DJ long-playing album. This was a brand-new idea! There was a growing market for 12" albums, so-called "packaged records", but only in the areas of classical music, Broadway shows, or jazz. There was no LP album from CHESS or any other rock-related company.

Freed sampled the 20 songs onto a single 33rmp record and had the film producing company DCA send this "Disc Jockey Sample - Not For Sale" LP out to more than 600 disk jockeys around the country. Here's a quote from DCA's marketing material:

Something completely new by way of exploitation is being tried on ROCK, ROCK, ROCK; an L.P. record containing all twenty-one songs from the picture has been pressed.We don't know how many DJs followed this advice. Alan Freed himself "world-premiered" this compilation on October 20th, 1956 on WINS. So it's safe to assume that the album was sent out by the end of October or early November 1956.

This record is going to every disc-jockey in the country with a letter asking him to set aside one evening in which to play the complete musical score from the picture. We further suggest that you contact your local disc-jockey and have him send out a press release stating that a premiere on disc will take place and have him mention the time and place.

Even though more than 600 copies of this very first Chuck Berry album have been pressed and distributed, very few seem to have survived. Most recipients probably either threw it away or played it to death.

The original album is extremely rare. Even the most detailed discography of Berry, Morten Reff's "The Chuck Berry International Directory" fails to show an image as does all of the Internet.

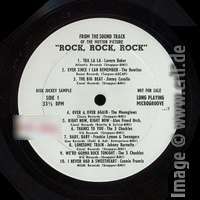

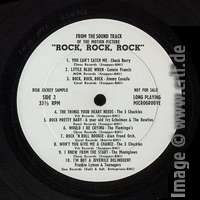

So here, for the first time on the net, images of cover and label of Chuck Berry's very first 33rpm LP album:

As you can see, there is an image of Berry as well as the line "SEE the inimitable Chuck Berry - HEAR him sing You Can't Catch Me". There is no back cover. That side is blank. There is no label nor any kind of catalog number. My best guess for a label name is the film company DCA. Morten Reff lists it under Roost, because the name of that record company is etched into the wax, as you can see on the high-resolution images. My guess is that Roost produced the album for DCA.

And there's even more: It seems that DCA included an 8 page, double letter-sized booklet with the promotional album. At least the copy I was lucky to get had this insert. The complete contents of this booklet is available as a PDF file here: http://www.alanfreed.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/063-King-Of-RockRoll-1956.pdf [If this link doesn't work, try http://www.alanfreed.com/wp/archives/archives-rocknroll-1951-1959/mp-rock-rock-rock/]. What the PDF misses is the original color of the title page as shown here:

If you want to know more about Freed and DCA marketing the movie, check out the other documents at alanfreed.com: http://www.alanfreed.com/wp/archives/archives-rocknroll-1951-1959/mp-rock-rock-rock/

The complete contents of this DJ sampler is as follows - with original label, composer, and publisher according to the film's music cue sheet. Some spellings differ from the album labels. Interestingly there are only 20 songs while the cover talks about 21.

- "Tra La La" - La Vern Baker (Atlantic Records, Johnny Parker, Snapper)

- "Ever Since I Can Remember" - Cirino and The Bowties (Roost Records, Ben Weisman and Aaron Schroeder, Tarpon)

- "The Big Beat" - Jimmy Cavallo's House Rockers (Coral Records, Glen Moore and Buddy Dufault, Snapper)

- "Over and Over Again" - The Moonglows (Chess Records, Ben Weisman and Al Weisman, Snapper)

- "Right Now, Right Now" - Alan Freed's Rock 'n Roll Band (Coral Records, Al Sears and Charles E. Calhoun, Sylvia & Bonita)

- "Thanks to You" - Teddy Randazzo & The Three Chuckles (Vik Records, Glen Moore, Snapper)

- "Baby, Baby" - Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers (Gee Records, Glen Moore and Milton Subotsky, Snapper)

- "Lonesome Train" - Johnny Burnette Trio (Coral Records, Glen Moore and Milton Subotsky, Snapper)

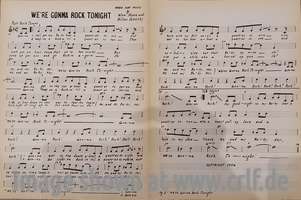

- "We're Going to Rock Tonight" - The Three Chuckles (Vik Records, Glen Moore and Milton Subotsky, Snapper)

- "I Never Had A Sweetheart" - Connie Francis (MGM Records, Glen Moore and Milton Subotsky, Snapper)

- "You Can't Catch Me" - Chuck Berry (Chess Records, Chuck Berry, Snapper)

- "Little Blue Wren" - Connie Francis (MGM Records, Glen Moore and Milton Subotsky, Snapper)

- "Rock, Rock, Rock" - Jimmy Cavallo's House Rockers (Coral Records, Glen Moore and Milton Subotsky, Snapper)

- "The Things Your Heart Needs" - Teddy Randazzo (Vik Records, Glen Moore and Milton Subotsky, Snapper)

- "Rock, Pretty Baby" - 6-year old Ivy Schulman (Roost Records, Glen Moore and Milton Subotsky, Snapper)

- "Would I Be Crying" - The Flamingos (Checker Records, Glen Moore, Snapper)

- "Rock'n Roll Boogie" - Alan Freed's Rock 'n Roll Band (Coral Records, Freddie Mitchell and Leroy Kirkland, Sylvia & Bonita)

- "Won't You Give Me A Chance" - The Three Chuckles (Vik Records, Glen Moore, Snapper)

- "I Knew From The Start" - The Moonglows (Chess Records, Glen Moore and Milton Subotsky, Snapper)

- "I'm Not A Juvenile Delinquent" - Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers (Gee Records, George Goldner, Kahl & Adt.)

In the original blog post from 2014 I had assumed that Milton Subotsky just like Alan Freed did not write any of these songs but just made a deal to get a share of the songwriter fees. This is incorrect!

Milton Subotsky indeed wrote the lyrics and sometimes the melodies to these and some other songs used in his films. Another example is Gene Vincent's Spaceship to Mars from It's Trad, Dad.

Courtesy of Subotsky's son Dmitri we are able to show some of the sheet music specifically written for this movie:

I'm sorry that I did disservice to the late Milton Subotsky by assuming that he was part of the dishonest industry around these early rock'n'roll films.

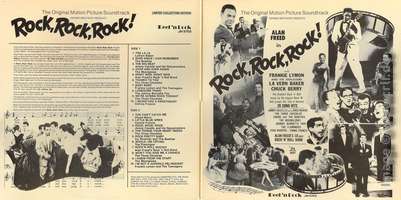

On a final note, there is a 1980s bootleg copy of this album on the Reel'n'Rock label (JN 5703) from Australia.

In contrast to the original album, the bootleg comes in a gatefold cover. It has a back cover with liner notes and a track listing, both of which are missing on Chuck Berry's very first LP album.

[Edit 17-07-2018: Links to alanfreed.com updated]

[Edit 11-08-2025: Corrected information about Milton Subotsky thanks to his son Dmitri.]

Friday, April 12. 2024

Peter OâNeilâs So-Called Disorder

For some years Peter has promised to publish his long and well-written articles on Chuck Berry as chapters in form of a book. And now Peter indeed published a book, though not the one we expected.

Peter is not only one of the greatest Chuck Berry fans, he also is a successful product liability attorney. And, as he recently found out, Peter is autistic. According to him, his diagnosis at the age of 65 years came as a surprise but concurrently explained a lot in his life.

So Peter decided to look back at his life and tell his readers about where his so-called âdisorderâ affected him, as seen from todayâs perspective. Peterâs book âMy So-Called Disorderâ (available at amazon) is a kind of memoir, though from a very specific point-of-view. Itâs an insiderâs view at autism and thus an extremely interesting read for both other people on the autistic spectrum and for people who havenât been diagnosed as such (yet) â and for those who simply are interested in this topic.

Peter explains how autism hindered him to take part in ânormalâ social life, even though he managed to get married (twice) and to have children. But on the other hand he explains how his autistic ability to focus on details, to think out-of-the-box, and to notice oddities which others overlook helped him to become a successful lawyer.

Due to partners and co-workers who might not have understood neurodiversity, but who understood that Peter needed a special environment to produce good work, he was able to fight huge companies on their defective products. A large part of this book explains the various trials, e.g. about exploding pick-up trucks and non-breakable scooters. For non-Americans this legalese is sometimes hard to understand â as the US legal system is as a whole.

But forty years of demonstrating complex relations to juries and courts â as well as an autistic ability to explain topics clearly without getting lost in too much context â help the reader to fully understand Peterâs points.

There isnât much Chuck Berry in this book except for some reports of concerts Peter visited. But besides bird watching and astronomy, the topic of Chuck Berry is clearly shown as one of the âspecial interestsâ which people on the autistic spectrum are said to have. However, if trying to know everything about Chuck Berry is a sign of autism, then I know of other âdisorderedâ collectors.

If you are interested to learn more about autism, this book is a very good item to start with. Highly recommended!

Wednesday, April 10. 2024

The Chuck Berry Sound according to Atomicat

Thus when Atomicat Records recently released a CD titled âThe Chuck Berry Soundâ, it was interesting to learn how they would define the sound that comes from Berryâs music. Well, they couldnât concentrate either.

At first they took the easy route: cover versions. Eight of the tracks are written by Berry himself and thus obviously close to his sound. However, Atomicat selected cover version you probably have never heard of before, even though all songs on this CD are from the 1950s and early 1960s.

Hear you can listen to one of the earliest female singers working with Berry material: Margaret Lewis singing Roll Over Beethoven. Another very early cover version from 1956, and a funny one, is Too Much Monkey Business by The Gadabouts supported by Carl Stevenâs Orchestra. Several of the cover versions are very different from Berryâs own, especially Betty Jean by Terry Gale, Brown Eyed Handsome Man by Scotty McKay, Carol by Jim Miller, and Rock'n'Roll Music by Jimmy Breedlove. Further cover versions included are Johnny B. Goode by Gootch Jackson with Herbie Layne's Orchestra and Thirty Days by Wes Reynolds, though titled Forty Days like the Ronnie Hawkins version.

A second set of tracks on this CD contains recordings which sound like Chuck Berry hits. Both Brownie McGheeâs Anna Mae, Rayvon Darnellâs Don't Want You Maybellene, and Buddy Lucasâ Oh Mary Ann were recorded in late 1955 and sound very much like Berryâs then hit Maybellene. Further soundalikes are Rhythm Feet by Carroll (Wild Red) Pegues which is similar to Around And Around, School Day Blues by Johnny And The Jammers (close to Brown Eyed Handsome Man), Pony Tail Girl by Glenn Garrison (Sweet Little Sixteen), and Knockin' On Your Door by Jimmy King (School Day). Two songs use the melody and pattern of Reelinâ And Rockinâ: Tiny Morrieâs Everybody Rocks and the non-twisting Mother Goose Twist by Oliver And The Twisters which by the way at 2:44 minutes is the longest of all the short songs on this album.

Most people will list Berryâs guitar playing as one or as the main element of âThe Chuck Berry Soundâ, ignoring that Berry reused guitar playing well-known before in Blues and Jazz. Anyway Atomicat identified guitar-oriented songs from the late 1950s and early 1960s on which the guitar players do not hide that they found these riffs on Berry records. Even though Atomicat tried to find the names of these guitarists, they did not succeed with every song. Some of the probably session musicians will remain anonymous.

Berry-inspired guitar solos can be found in Dee Clarkâs Dance On Little Girl (guitar: Phil Upchurch) and The New Blockbustersâ Rock & Roll Guitar Part 1 (guitar: Paul Buskirk). On Ray Sharpeâs Justine, Tony Casanovaâs (i.e. Jutillo Perezâ) Showdown and Billy Peekâs Rock To The Top the main artists both sing and play the Berry guitar. Unknown guitarist provide Berry-like guitar playing on Buddy Howardâs Take Your Hands Off Me Baby, Jerry Hawkinsâ Swing Daddy Swing, and The Jet Tonesâ Henry.

If you want to count Caveman by Tommy Roe and The Satins as a Berry soundalike is doubtful, though, at least to me. And to accept Eddie Clearwaterâs I Was Gone here requires you to know that Edward Harrington (his real name) was not only a Berry soundalike (with many other recordings and cover versions) but also a Berry lookalike in his 1960s shows.

The remaining three songs from this 30-track CD are tribute songs to Chuck Berry himself or to his best-known protagonist. The Dusters sing about a show with both Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis (Rock At The Hop, 1961). Leonard Douglas Drake under his alias Big Daddy G in 1963 recorded a tribute song called Big Berry (Boss Man Guitar) in which he combines Berry song titles. Finally Eddy Bell and the Bel-Aires from 1961 continue the Johnny B. Goode saga with Johnny Be-Goode Is In Hollywood.

All in all âThe Chuck Berry Soundâ (Atomicat Records ACCD162) is an interesting selection of recordings which show Berryâs influence on other musicians. All these were released long before the Beat craze when all the successful bands listed Berry as one of their main influencers. The latest recording on this set is from 1963. while the earliest start close after Berryâs first chart hit. This is not a CD you will play over and over, but itâs a rare chance to listen to fairly old and hard to find Berry-inspired music.

Tuesday, January 16. 2024

The Chuck Berry Vinyl Bootlegs, Vol. 3: America's Hottest Wax

This series of articles is going to describe the Chuck Berry vinyl bootlegs released in the 1970's and 1980's. For any record collector these items are important to know of, even though you don't necessarily need to have them. Omitted from all the usual discographies, information about these records is next to void. Given the secret nature of the bootlegger business there are no exact dates, numbers, or origins. I have tried to collect this information from various sources and mostly from my own collection of records. If you can add anything of worth to the information given here, I'd be glad to know!

This is the third part of this series and it covers another typical kind of bootleg record: a record containing studio outtakes.

Chuck Berry - America's Hottest Wax - Reelin' 001

[This blog post appeared here first in September 2015. Due to the 2023 release of Daniel Nooger's book "Belly of the Beast - Chess Records, the All Platinum Years" we have to add some details which also answer some of the questions the original text left open.]

Besides live concert recordings, the most interesting bootlegs are those which contain studio material not to be found on legal releases. Typically these are outtakes or versions of songs not good enough to be officially published by the record companies. You may wonder how bootleggers can get access to such unreleased material. There are many ways. Sometimes the artists themselves give tapes out of hand, sometimes the housekeeper finds some tape in a paper bin. In this case we know when, how and by whom the previously unreleased tracks were found and combined. We don't know, though, how they got into the hands of bootleggers.

Anyway, this record contains ten Chuck Berry recordings from the 1950's and early 1960's which had not been released before. There were two additional recordings which had been released before but only with fake audience noise. And there were two recordings released by the vocal group The Ecuadors on which Berry's contribution hadn't been known before.

During the mid to end 1970s Dan Nooger worked for All Platinum Records who had bought the Chess archives in August 1975. Dan's job was to search through the old tapes to find, combine, and release new records under the Chess name. He created some interesting releases containing known and unknown recordings from the Blues and Jazz masters Chess had stored.

All Platinum went bankrupt in 1979. The same owners, Sylvia and Joe Robinson, immediately formed a new label, Sugar Hill Records, taking over the Chess archives until they got in a legal dispute with their distributor MCA and lost the rights to the Chess catalogue during the mid 1980s.

The only Chuck Berry record which came out of All Platinum/Sugar Hill was The Great Twenty-Eight (CH-8201, 1982), which contained just the well-known hits. But Dan Nooger had found unreleased Chuck Berry material within the archived master and session tapes.

In his book, Dan tells:

In the course of preparing some future releases, I went through the master book and session tapes looking for unissued tracks by Chuck. There werenât too many, but as an example, on the December 1955 session which produced âYou Canât Catch Meââ and âNo Money Downâ I found on the master reel a slow blues, âIâve Changedâ, which was recorded between them. It lay forgotten, with no master number assigned and never pulled out as a filler for one of Chuckâs albums, but it was one of his finest blues performances. More good alternate takes surfaced from some of the later sessions. Berryâs first take performance of âReelinâ & Rockinâââ (with some different lyrics from the final version) which was on an undated session reel just labeled âC.Bâ, inspired Leonard to call out, âThis is good just the way it is!â Chuck, ever cool, just responded, âOh, yeah?â. There were a brace of tracks which were original versions of sides eventually released on the fake âliveâ album âChuck Berry on Stageâ (minus the dubbed audience noise), and even a master tape by a group called the Equadors, whose âLet Me Sleep Womanâ / âSay Youâll Be Mineâ featured Chuck on guitar (and although credited to âR. Butlerâ on the original Argo single, the songs were published by âChuck Berry Musicâ). Another session tape just labeled âC.B. â 21â yielded a whole session rundown of an unissued song originally slated as âVacation Timeâ; after 10 or so takes the arrangement was changed from straight up rock to a blues format. I labeled them â21â and â21 Bluesâ. Eventually I pulled together an albumâs worth of material.

This master tape Dan collected is obviously the origin of the bootleg we talk about here. It was prepared for an All Platinum release, though never produced.

Three variants of this bootleg exist. One of these is not a bootleg at all.

The first variant had a blank white cover onto which the record name America's Hottest Wax as well as the label name and number Reelin' 001 were rubberstamped by hand.

The labels are completely blank and have a light pink color. The master number as etched into the dead wax reads CE 70/1.

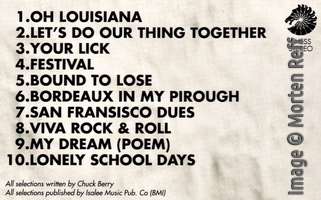

My copy didn't have any other information with it. Morten Reff was so kind and sent me a copy of a sheet of paper which came with his record.

The sheet contains nothing more than the track listing and a few details about each song.

The tracks on this record are as follows (spelling as on the sheet):

Side 1

- ROCK & ROLL MUSIC (unr. demo version)

- CHILDHOOD SWEETHEART (unr. alt. take)

- 21 (Vacation Time) (unr.)

- LET ME SLEEP WOMAN (Ecuadors)

- DO YOU LOVE ME (unr. alt. take)

- 21 BLUES (Vacation Time) (unr.)

- ONE O'CLOCK JUMP (unr.)

Side 2

- REELIN' AND ROCKIN' (unr. demo version)

- SWEET LITTLE SIXTEEN (unr. alt. take)

- BROWN-EYED HANDSOME MAN (without dubbed audience)

- SAY YOU'LL BE MINE (Ecuadors)

- I'VE CHANGED (unr.)

- 13 QUESTION METHOD (unr. alt.take)

- HOW HIGH THE MOON (without dubbed audience)

Morten Reff dates this bootleg at appr. 1979 and variant 2 (below) at 1980. To me variant 1 looks at least some years older. Label and cover look more like an early 1970's bootleg. However, since Nooger's other Chess releases came out in 1976 onwards, 1977 to 1979 probably is the correct timeframe.

Variant 2 has a fully printed cover, a printed label and liner notes. And it shows more than a dozen previously unreleased photos (also from the Chess archives?).

The front cover tells artist and record name. Also it says "rare and unreleased tracks 1955-1963". The label name is now written as reelin' with a lower-case R.

Next to the photos and track listing the back cover contains a quote from an interview with Keith Richards, printed in the January 1979 issue of Rock&Folk magazine in which the interviewer claims to have listened to a cassette tape containing some of the recordings included.

The cassette tape mentioned originates from Dan Nooger, as he tells in his book:

I copied the material onto a cassette. After I landed at Atlantic Records, I ran off a copy for one of our publicity guys, Art Collins, who was assigned to go out on the road with the Rolling Stonesâ 1978 âSome Girlsâ tour. One day I got a frantic call from Art; he had played the tape for the Stones and he was flying back to New York next day and I was to have maybe seven copies run off for him to bring back for the Stones touring party. He flew in, handed me a âSome Girlsâ press kit cover autographed by all of the Stones plus Ian Stewart and Ian McLagan (which immediately went straight into a frame and up on my living room wall), and off he went. Art eventually got kicked upstairs as a vice president with Rolling Stones Records. Several months later, I was reading an interview with Keith in Rock & Folk, a French music magazine; the tail end of the story had Keith pulling the cassette from his travel bag and excitedly playing it for the interviewer (âWait! I want to play you some Chuck Berry, I have unreleased tapes that youâll loveâ). What Iâd like to know is if Keith ever played it for Chuck during the production of the Hail! Hail! Rock ân Roll film, and what Chuck may have thought of it. Keith, if youâre reading this, get in touchâŠ

The January 1979 quote places the publication date of variant 2 to 1979 or later. This is a complete new record from a new master disk. The etching on the dead wax now reads 001-A/B.

It is interesting to note that the printed track listing on the back cover differs in some details from the insert sheet of variant 1. And even more interestingly variant 1 contains the more correct information. Among the errors on variant 2 are the spelling of the Ecuadors and suppressing the previous release of the dubbed tracks.

The same errors were repeated character by character when in 1983 CHESS (UK), at that time a label of PRT Ltd., released CHESS CXMP 2011. Probably due to the huge success of the bootleg, CHESS (UK) decided to release the exact same contents on an official album.

The cover does not tell so. It calls the record just "Chuck Berry" as part of PRT's "CHESS masters" series. However, when you look at the record labels, you'll see the name "America's Hottest Wax" printed.

One has to note that while the official CHESS (UK) release contains the exact same sequence of the tracks, they do not always sound exactly alike. Sometimes the songs on the official release fade later than on the bootleg. This might point to the fact that PRT indeed used the original CHESS tapes for mastering this album. All Platinum/Sugar Hill had good contacts with UK record companies. Phonogram had co-financed the Chess archives purchase, Charly got all their Chuck Berry material from All Platinum, PRT was the new name for Pye Records who originally released Chuck Berry in the UK. Maybe PRT had access to Nooger's original master tape while the two bootlegs result from the cassette copy - we'll never know.

To read the other parts of this series on Chuck Berry vinyl bootlegs, click here:

Friday, January 12. 2024

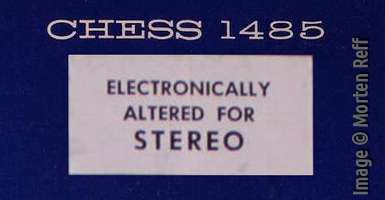

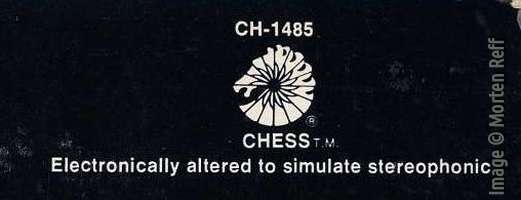

Chuck Berry in Fake Stereo

In the second half of the 1960s, with the popularity of Stereo albums and FM radio, Mono records sounded outdated and dull. Record companies trying to re-sell 1950s hits therefore used a trick to create fake stereo versions of recordings originally made and only available in Mono.

The old recordings were âelectronically reprocessed for stereoâ. Technically the original mono signal was copied to both stereo channels. On one channel the higher tones were enhanced, on the other the lower tones. One channel was delayed a tiny fraction of a second and artificial echo and reverb were used to mask this delay. Unfortunately this distorts the original recording to an amount which makes them sound ugly when compared to the original mono mix.

During the 1970s many re-issues of Berry material contained such fake stereo which is why record collectors omit them to the most part. At least some of the fake stereo releases came with a tiny warning as shown in these cover segments.

Cover details of 1970s fake stereo releases

If you were following the hype around the Beatlesâ ânewâ recording âNow and Thenâ, you learned that nowadays computers are able to separate John Lennonâs piano playing from his singing based on a source tape where these two blend into each other. The trick is to find notes and frequencies which are typical to a male singer and to find notes and frequencies which are typical to a piano. A human listener can do so easily and tell exactly what is singing and what is piano playing. Computers are not that good.

However, new computer techniques approximate the identification of a songâs parts. The trick is to have a computer analyze thousands or millions of piano recordings and to find patterns which are typical to piano playing. This is pure statistics, technically called machine learning, or for the marketing folks âartificial intelligenceâ. Given enough training data, you can teach the software to identify piano playing, male or female vocals, drums, guitar, saxes, and so on.

There is free and commercial software available which does a pretty good job at identifying and separating instruments from a recording mix. However, such a result is never perfect. Even a human listener might get fooled, when a talented vocalist mimics a saxophone solo. Certain sounds can be created using different instruments alike such as a bass line played on the lower strings of a guitar. Especially pianos are difficult to identify as they have a very wide range of tones which can sound like a guitar or even like some drum set segments. And of course it is very hard to separate two guitars or two pianos.

If you separate the musical instruments used during the original recording, you can re-use the extracted tracks to combine them with other recordings just like they did with the Beatles song. Or you can re-mix the individual elements at varying intensities and delays to two separate tracks which build the left and right channel of a stereo release.

Hit Parade Records of Canada for some time already uses this re-stereofication method to create fake stereo versions of 1950s hits. A first fake stereo version of a Berry hit (âSweet Little Sixteenâ) appeared in 2020.

In 2023 Hit Parade Records released the CD album âChuck Berry Stereo: 27 Original Hitsâ containing 22 of such fake stereo versions. The other five songs are stereo versions originally released on the 1960s Chess albums. âRoute 66â is fake stereo, even though a true stereo recording of an alternative take exists.

The CD cover does not mention the artificial nature of the versions. This âfakeâ aspect is hidden on the last page of the booklet.

So now we can listen to songs such as âMaybelleneâ or âJohnny B. Goodeâ in stereo. And just like in the 1970s, these fake stereo versions are much worse than the original releases. For the most part we hear the lead guitar at one end of the stereo range and the cymbals from the drum set at the opposite end. Everything else is more or less in the center with the vocals quite low in the mix. The marketing material shouts that ânow you can hear guitar notes come to life that were previously buried in the mono mixesâ but this goes with the consequence of other elements now getting buried instead.

As said, given the original mixed material a separation cannot be perfect. Here we hear notes from the same guitar sometimes from the left, sometimes from the center, sometimes even from the complete other side of the room which sounds as if there were more guitars present in the studio as there really were. On the other hand it sounds as if there were only cymbals on the drum kit but no drums at all, a woolly sound on the drums altogether. And especially problematic is the piano, which sounds as if it were moved around the studio during a songâs recording take. In general there is too much echo just like it were with the 1970s fake stereo releases. One positive note, though: What they did really good was the separation of Berryâs lead vocal and the chorus on âAlmost Grownâ. This sounds as if the vocal group is standing to the side as it probably was originally.

All in all these versions are nothing a collector would want. On the contrary: just as in the 1970s, where the original mono recordings were replaced by the fake âelectronic stereoâ variants, the same also applies here. As soon as streaming services or re-issuers learn of the existence of these so-called âtrueâ stereo versions, how long will it be before the original mono versions are replaced?

Morten Reff adds: âJust to compare a little. I also bought the new âChirping Cricketsâ (the first LP by Buddy Holly And The Crickets from 1958) on Rollercoaster Records in âstereoâ, and they did a much better job of it. Clearer and better sound and better stereo effect. Although I must admit that I still go for the original mono versions.â

Monday, March 13. 2023

Little Queenie overdubs

We believe thereâs a ride cymbal over dub on the original version, what do you think? Because you can hear drum fills and the ride cymbal continues.

As even Odie Payne couldnât play a two-handed drum fill and a cymbal in parallel, this is a very valid comment. Martyâs email triggered some in-depth investigations and a huge number of emails floating between the contributors to this site.

Todayâs technical possibilities allow you to extract, modify and single out parts of a historical recording. This allowed our technical expert Arne Wolfswinkel to both verify Martyâs findings and to discover some additional astonishing facts.

You should know that besides the original 1958 record release we have another, slightly different take of Berryâs classic tune. This âpreviously unreleased versionâ (later called âTake 8â) of Little Queenie came into light in 1986, when Steve Hoffman presented to us lost recordings from the vaults of Chess Records. (âRockânâRoll Raritiesâ, CHESS CH2-92521)

Overdubbing was a common practice with Chuck Berryâs recordings at Jack Wienerâs Sheldon Recording Studios. That way the producers could add more Chuck Berry guitar to a recording or more Chuck Berry voice. Even a classic such as Johnny B. Goode was created in such a two-step process. (See the blog article âThe Johnny B. Goode Sessionâ)

Overdubbing means that a first recording was made using the full band. During recording, Berry played some of the guitar elements and sung the main vocal. Later the engineer and Berry worked out the finer details such as additional guitar solos or a second voice without the need of the band. The engineer played back a tape containing the original base track, Berry sang or played, and the result was recorded to a second tape. This procedure was necessary, because in the 1950s Chess could not record multiple instruments separately and mix them later.

One example for a guitar and vocal overdub is take 9A of Merry Christmas Baby from the Little Queenie session. This is the variant released on Chess single 1714.

With Little Queenie this overdubbing happened a bit differently. As Marty found, some parts of the drums were recorded for the base track while other parts were recorded during the overdub. And comparing the two slightly different takes of Little Queenie which survived, it becomes obvious that in this session the overdubbing involved not just Berry or Odie Payne, but also Lafayette Leake.

Both takes of Little Queenie are based on the same base track which consists of Berry playing rhythm guitar, Willie Dixon playing double bass and Odie Payne playing the drum rhythm. This base track is 100% identical on both takes.

Different, and thus overdubbed onto this base track, is Berryâs singing, some additional guitar playing, Odie Payneâs cymbal or hi-hat, and Lafayette Leakeâs piano. As due to sound degeneration overdubbing was reasonable only onto the first-generation tape, we have to imagine that Berry, Payne, and Leake on this 19th November 1958 were listening to the base track and together added their overdubs.

The correct recording details for both takes of Little Queenie will therefore be:

Chuck Berry guitar, vocal (overdub), 2nd guitar (overdub)

Ellis "Lafayette" Leake piano (overdub)

Willie Dixon double bass

Odie Payne drums, additional drums (overdub)

We will alter our database accordingly. We will keep the âTake 8â distinction for the alternative even though it is completely unclear where it comes from. The count-in preceding the song (âAre you ready, Chuck?â) on the 1986 album is probably not from the original tape as the guitar intro overlaps the engineerâs announcement which would usually result in an immediate stop to the recording. It is known that Steve Hoffman shuffled such segments around and even created completely new songs from segments of different takes. (For details, read the blog posts âSweet Little Eight Variants of Sweet Little Sixteenâ and âChuck Berry in Stereoâ)

[addition 08.01.2024: Those who know have found that the take 8 introduction has been taken by Steve Hoffman from a tape containing the recording takes of Sweet Little Rock and Roller.]

Run Rudolph Run from the same session uses the same melody and the same rhythm as Little Queenie. And here as well we hear both a guitar overdub and additional cymbal or hi-hat playing.

We would like to thank reader Marty for finding the cymbal overdub and especially for telling us.

Tuesday, January 31. 2023

Lonely School Days - the variants explained

Sometimes a second recording was made for commercial reasons, e.g. when a new record company tried to generate additional income from old songs. A typical example is Roll Over Beethoven, initially recorded in 1956 in Chicago for Chess Records, re-recorded 1966 in Clayton for Mercury Records.

Sometimes a second recording was made for artistic reasons when Berry tried to make a song sound better or at least different. See for instance Havana Moon, initially recorded in 1956, then in 1979, and finally in the late 1990s.

In addition, songs evolve over time during the recording process itself until a final version pleases both artist and company. See for instance the song recorded as 21 (Twenty-One) of which some studio tapes survived. There are fairly different variants until a final result was reached and published under the title Vacation Time.

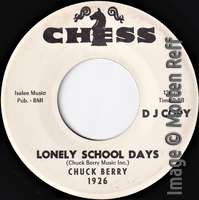

Lonely School Days is another song which evolved over time. One surviving variant has been recorded in late 1964 and released on the back of Chess single 1926, Dear Dad, published in March 1965. This variant is a slow, emotional song. It can be easily identified by the prominent use of a sax, probably played by Bill Hamilton. This variant is almost three minutes long and commonly referred to as the "Slow Version".

B side of CHESS single 1926 (DJ Copy)

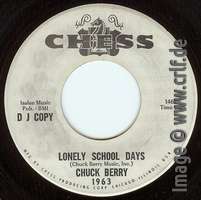

Somebody really liked this song. Just one and a half years later it made it again to the song list of a recording session. In the spring of 1966, a second variant of Lonely School Days was cut. This time it had no sax, but more guitars. Most importantly it was much more rocking, played much faster. Singing the same song at much higher speed reduces the run length to a little over 2:30 minutes.

Surprisingly, this "Fast Version" immediately was used again as the B side of a Chess single. Chess 1963 having Ramona, Say Yes on the plug side was released in June 1966. So we have two Chess singles, released not far apart, having the same song in two different versions.

B side of CHESS single 1963 (DJ Copy)

Soon after the release of the second single, Chuck Berry left Chess Records to work for Mercury. The "Slow Version" never made it to a contemporary album. Only in the late eighties and nineties it was found on some rare LP albums.

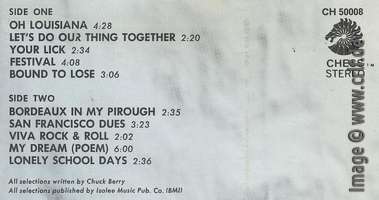

However, the "Fast Version" was included on an official Chess album: San Francisco Dues (Chess 50008) was published in 1971, five years after the song's initial release. Berry had returned to Chess and to fill his second new album a few recordings were added which had not made it to LPs before. Interestingly the LP contained a Stereo mix of the "Fast Version" while both singles had been in Mono - as were all Chess singles in the 1960s.

This is the track listing from the back of San Francisco Dues (Chess 50008) containing the Stereo mix of the shorter, fast version.

Remember: San Francisco Dues contained the Stereo mix of the "Fast Version". Simple, isn't it?

However, who listens to Vinyl albums any more? If you listen to San Francisco Dues from one of the streaming services, Lonely School Days isn't fast at all. Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube all play the "Slow Version" as part of San Francisco Dues. Due to this a reader recently emailed and wanted us to correct our database of all Chuck Berry recordings. We are happy for every hint or correction, but here we refused to do any changes, as our listing is correct!

How can it happen that online services play the wrong song - all of them alike? This is due to how they get their playing lists. Record labels such as Universal provide the streaming platforms with the files to play. If the record company is in error, so are all their customers.

We assume that this specific error was introduced as early as 2013. That year Universal in the U.S. published a CD re-release of San Francisco Dues (Geffen GET-54058-CD). And on this re-release they included the wrong variant of Lonely School Days. Morten Reff noticed this and complained about it in his review on this blog soon thereafter. It was not the only thing to complain about: Over and over on label, box, and booklet the company managed to spell "San Fransisco" with an s! One really has to wonder about quality control at Universal.

This is the track listing from the back of Geffen's CD re-issue of San Francisco Dues (Geffen GET-54058-CD) containing the wrong version. Note the mis-spelling of San Francisco and the missing run lengths.

Universal in Japan did a much better job with their re-release of San Francisco Dues (Geffen UICY-94635). They not only included the correct "Fast Version" where it belonged, they also added three bonus tracks: the "Slow Version" in Mono and two different mixes of Ramona, Say Yes.

Moral of the story: In today's digital world errors reproduce fast and are hard to correct. Always double-check with a reliable source.

Many thanks to reader Andy for pointing us to the error in the streaming services - though not for complaining about our database

[Addition by reader Andy: "I should mention that my initial email was actually a failed attempt at correction rather than a complaint. Why would I ever complain about so meticulous and thorough a database regarding one of my favorite artists? Keep up the good work."]

Sunday, January 29. 2023

An Interview with Johnnie Johnson - 1987

This site's contributor Morten Reff and the Berry fans Johan Hasselberg and Thomas Einarsson had the opportunity to talk to Johnnie Johnson, long-time partner and pianist for Chuck Berry. Thanks to Morten and Johan we can reprint the questions and answers.

Left to right: Morten Reff, Johnnie Johnson, Thomas Einarsson, Johan Hasselberg, and Herman Jackson at the Park Hotel in BĂ„stad, Sweden, July 5, 1987. Herman was Chuck Berry's drummer during the summer 1987 tour. Thomas had done a painting by Chuck Berry that he handed over to Johnnie Johnson.

Photo: Carl Hasselberg

The interview is made over a cup of coffee at the hotel's outdoor seating. Johnnie takes a big chunk of coffee and starts telling about himself:

I was born in West Virginia on July 8, 1924. When I went to school I played piano, drums, and bass. But piano was my main instrument. I was in a High School band until 1943, when I started my military service at the navy. When I pulled out in 1946, I started my first own band. In 1949 I moved to Chicago, and then on to St. Louis.

DID YOU PLAY MOSTLY RHYTHM & BLUES?

Well, most of the time there were nothing but standard songs, such as "Stardust", "Body and Soul", Sunny Side of the Street", or whatever. It was before this rhythm & blues breakthrough.

WHAT PIANISTS DID YOU LISTEN TO AT THIS TIME?

I'm a Oscar Peterson-fantast. Yeah! Oscar Peterson, Errol Garner, and Pete Johnson. Pete Johnson was my first favorite. It was late 1930's and 1940's. I used to play a Pete Johnson song, called "627 Stomp". That was my signature then.

HOW DID YOU TO GET IN CONTACT WITH CHUCK BERRY?

I heard him at a club in East St. Louis called Hoff's Garden. I liked the way he played the guitar. One evening when I was playing, my saxophonist became ill. I called Chuck and asked if he could have the possibility to play the guitar. And he said, "sure, I can play". He came home to me and we played through the songs and then we drove to the show.

Chuck Berry in concert, Norrvikens TrÀdgÄrdar, BÄstad, Sweden, July 5, 1987

Photo: Johan Hasselberg

WHO PLAYED THE SAXOPHONE IN THE JOHNNIE JOHNSON TRIO?

His name was Alvin Bennett. But it was only until 1954. Now he is paralyzed. He can't even... yes, you know.

WAS IT A BASS PLAYER IN THE BAND?

No, it was drums, piano, and saxophone, and then guitar when Chuck came along. We played most at Club Cosmopolitan in East St. Louis. Ebbie Hardy, who played drums, suffered a heart attack and died a few years ago (1983).

CHANGED THE BAND NAME WHEN CHUCK CAME?

No, it was still called The Johnnie Johnson Trio. It was only when Chuck went to Chicago and met Leonard Chess we renamed the band. We recorded the single "Maybellene" and Chuck said, "Johnnie, is it okay that I call it The Chuck Berry Combo?". I said, "Of course, you paid the gas to Chicago", and then it became The Chuck Berry Combo.

Left to right: Chuck Berry, George French, Johnnie Johnson in concert, Norrvikens TrÀdgÄrdar, BÄstad, Sweden, July 5, 1987

Photo: Bo Berglind

YOU PLAY A MELODY ON THE PIANO ON MANY OF CHUCK BERRY'S SONGS.

That's what Chuck Berry wanted me to play. I play as I feel so everything rolls smoothly, just like ice cream on a cream cake!

IT WORKS AS A SOLO INSTRUMENT.

That's right and that's what Chuck Berry likes with my pianoplaying. That's why he doesn't like someone else's pianoplaying than mine! Let me give a good example. Chuck and I have recorded some songs that have not been released. For example, Frog's "Good Times Boogie" and "Honky Tonk Train". It was in the 1950's. It was my music style, but Chuck and I could play together and it sounded like Chuck Berry's music. Chuck is still playing some jazz, as for example, "Jazz at the Philharmonic". He plays all kinds of music!

DO YOU STILL PLAY IN THE CLUBS IN ST. LOUIS?

Yes, three nights a week.

DO YOU PLAY ALONE OR DO YOU HAVE A BAND?

I have a band called Johnnie Johnson & The Magnificent Four, and when Chuck comes to town he plays with us.

WHAT REPERTOIRE DO YOU HAVE?

There are blues, jazz, rhythm & blues, and usually rock when Chuck visit us.

DO YOU EVEN SING?

No, no, I can always talk, but do not sing!

YOU HAVE BEEN AWARDED A DISTINCTION AT ROCK & ROLL HALL OF FAME.

Yes, I was chosen as the fourth biggest rock'n'roll pianist throughout the ages. It was Fats Domino, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and myself. I didn't know about it, but they sent me a magazine afterwards.

THANK YOU, JOHNNIE !!

Thank you, I hope to see you again!

And, Johan tells, they met again: "Johnnie gave me his address and two years later I greeted him in St. Louis, and listened to Johnnie Johnson & The Magnificent Four."

Many thanks to Morten and Johan for sharing these memories with us!

Thursday, January 12. 2023

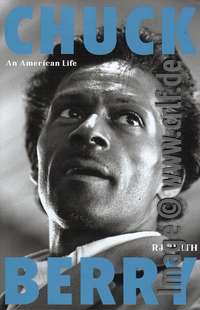

Chuck Berry: An American Life - by RJ Smith

âWhat we have is more interesting. A choice of threading through the details of his life or working around them completely â your call! - and simply hearing him. To pull the joy and poetry out of the music he created and have it take us where it wants to go â not where he went. To live our lives with it, and not live his life. Thatâs a lot.â

As the creators of this website we have made our choice a long time ago. These pages here are about the music of Chuck Berry and only about his music. We do not discuss any other aspects of Berryâs life in this blog or on the main page. For us there were at least two very good reasons for this decision. For one, we are deeply convinced that Berryâs music is much more entertaining than his criminal, sexual and business affairs. And secondly we think that with recordings and records we have at least a small factual base to build our research upon. RJ Smith in his new âChuck Berry: An American Lifeâ decided to concentrate on all the other stuff instead.

Chuck Berry was a control freak, a sex maniac and business-wise everything but a nice person. His criminal records included armed robbery, tax evasion, and what we would call today child abuse, plus many more. All this is no new news. We have read about these in newspapers and books as well as all over the Internet.

RJ Smith quotes Berry saying he wants the people to tell the truth about him. But there are many truths. There is the truth about a strange man with a weird character and perverse habits. But there also is the truth about the musical artist whose output had a huge impact on what became popular music during the last 70 years.

It might have been interesting to discuss Berryâs personality from a psychological perspective. Or it might have been interesting to analyze how this pathological mindset affected Berryâs music or lyrics.

None of this you will find in this book, though. Instead RJ Smith has taken a huge effort to document Berryâs failings. Most has been known before and is documented in detail e.g. in Bruce Peggâs excellent biography. Smith dug even deeper into court documents and he tried to get quotes from witnesses not published before. However, most of the contents is a simple repetition from old sources such as Berryâs own autobiography â even repeating errors included.

Where Smithâs book enhances the previously published biographies is the coverage of Berryâs last years. Thatâs the advantage of a biographer who waits until his subject has deceased. So here we get a few additional pages about his latest tours, the release of his last record, and we learn how his family declared Berry incompetent.

Smith in many aspects tries to write a different biography and succeeds in doing so. He completely concentrates on Berryâs personal and business matters, almost ignoring his musical work. Only for one song Smith reserves a complete chapter: My Ding-A-Ling. And again the author accomplishes something different as this song was left out of any serious discussion about Berryâs Ćuvre so far.

One peculiarity of this text is a bit confusing for European readers: All over the book RJ Smith tries to find arguments to justify Berryâs behavior as a result of black versus white America. As being no part of the American society, we are not qualified to judge on RJâs findings. From a musical point-of-view I think it is a bit far fetched to locate racially related hints in the lyrics of e.g. Promised Land.

Is this a book you want to read? If you love Chuck Berry, donât do it. If you are interested in Chuck Berryâs music, thereâs nothing to gain from reading it. But if you want to learn about Berryâs porn collection or any other aspect of his life, thereâs almost too much information in âChuck Berry: An American Lifeâ. But in the end it definitely is âyour callâ: a choice of threading through the details of his life or working around them completely.

âChuck Berry: An American Lifeâ by RJ Smith (Hachette Books, ISBN 978-0-306-92163-6) is available in every better book store near you.

Monday, June 27. 2022

Chuck Berry - Live from Blueberry Hill - explained

Since 1996 Berry had played regular shows at Joe Edwards "Blueberry Hill" in St. Louis, more than 200 of them. In contrast to the huge concert halls typically used for Berry concerts, the 300-seat "Duck Room" brought back the club atmosphere from the 1950 when Berry started to perform in St. Louis.

Also in contrast to his other concerts world-wide, the Blueberry Hill shows always had the same line-up for almost twenty years. The "Blueberry Hill Band" consisted of Berry's children Charles, Jr. and Ingrid, his band leader and bass player for 40+ years Jim Marsala, plus Robert Lohr on piano and Keith Robinson on drums.

As we already know from Dualtone Music, "Live from Blueberry Hill" is sold in many different ways: on CD, as a digital download, and in various Vinyl variants. The music is always the same, and this is what this site is about.

The liner notes to the CD tell a bit about the shows, but very little about the music. There's not even a recording date given, just "All songs recorded live at Blueberry Hill, St. Louis, MO from July 2005 - January 2006". I therefore contacted Bob Lohr, who played piano on all tracks, to find out more about how the recordings were created. Here's what I learned.

Bob Lohr (to the right) and the band (Jim Marsala, Charles, Ingrid, and Chuck Berry) live at the Blueberry Hill 2009

photos courtesy of Doug Spaur, many thanks, Doug! Click to enlarge.

Bob, do you remember when you started playing with Chuck at the Blueberry Hill or at other venues?

1996âŠon Chuckâs 70th birthday. The first three shows were in a different club room at Blueberry Hill called the Elvis RoomâŠcould probably fit 100 people maximumâŠabout the size of a basement recreation room w/ Elvis memorabilia in glass cases on the walls. Joe Edwards later built the Duck Room in 1997 after he took over an adjoining restaurant (Ciceroâs) which moved up the street. Ciceroâs had a music club in the basement which was very smallâŠhad a lot of local acts plus well known national acts occasionally (I played there in local blues bandsâŠalso saw the Doorsâ Ray Manzarek live w/ poet Michael McClure once!). Joe Edwards expanded Ciceroâs club space, including digging out the floor a couple of feet deeperâŠand the Duck Room was born!

Please tell our readers a bit about your musical work. How often did you perform with Chuck, with whom did you share stages?

With Chuck I played almost all the shows at Blueberry Hill (over 200) and at least 100 on the road/private gigs/local gigs outside of Blueberry HillâŠan estimate would be some 350 shows in total.

Onstage, Iâve gigged w/ Willie âBig Eyesâ Smith & Calvin âFuzzâ Jones (Muddy Waters rhythm section), Billy Boy Arnold, Jimmy Rogers, Sam Lay, Roy Gaines, Snooky Pryor, Hubert Sumlin, Albert Collins, Big Jack Johnson, Sam Carr, Mud Morganfield, Cyril Nevilleâs Royal Southern Brotherhood & many others. Lots of well-known blues artists over the years.

Hereâs a partial discography on me: https://www.allmusic.com/artist/bob-lohr-mn0000057405

Thinking back at the Blueberry Hill shows, what made them special in comparison to playing at large halls?

It was a 300-seat venue which made it a more intimate experience for the fansâŠthe St. Louis version of Liverpoolâs Cavern Club. Chuck always had a lot of interaction with audiences wherever he playedâŠcheck out various YouTube clips. People flew in from all over the world to see Chuck at Blueberry Hill. After tickets became obtainable online, people would come up to me after the show from all over the world. Oftentimes I would take them to downtown St. Louis to either BBâs Jazz Blues & Soups or Beale on Broadway to hear some serious blues/r&b. A lot of these tourists were traveling through what I call âBlues/Rock Ground Zeroâ, or hitting all the music cities within a 300-mile radius of St. Louis: Chicago, Memphis/Clarksdale, Nashville etcâŠ

The new CD presents a short show of just 30 minutes. Was this the standard length of the Blueberry Hill performances?

No, Chuckâs standard show was 1 hour wherever we played.

30 minutes seem to become the new standard for albums. Given that many people listen to music using digital streaming, 30 minutes seems to be "long enough" for the labels and for the listener's attention span.

As for the song selection, we only hear Chuck's greatest hits plus Walter Jacobs' "Mean Old World". Was this a typical tracklist?

No, we did at least two or three blues numbers per gig. âWee Wee Hoursâ of courseâŠalso âIt Hurts Me Tooâ and âKey To The Highwayâ, âEvery Day I Have The Bluesâ, âWorried Life Bluesâ, âBeer Drinkinâ Womanâ etc.

Do you remember Chuck playing more obscure and rare songs from his huge repertoire? On the CHUCK album for instance there's a Blueberry Hill recording of Tony White's "Enchiladas".

Not reallyâŠwould usually play the well known songs.

What do you think is missing from new CD? Is there any special song you remember from Blueberry Hill which you wished to hear again?

We used to do âBrown Eyed Handsome Manâ and âPromised Landâ on an occasional basisâŠalso, âWorried Life BluesââŠ

Ingrid is heard only on two tracks, "Mean Old Word" and "Let It Rock". Was it typical that she only joined small segments of the show? Or has she been with you only sometimes and was absent when the other tracks were recorded?

She was at every show in St. Louis onstage. She did not go on every road trip.

The two songs Ingrid plays harmonica on as well as "Roll Over Beethoven" are also the only three songs on this album we hear you soloing. Have you been allowed to solo during the shows? Or was it just Chuck and the rhythm he needed?

As you can hear on the latest live CD, Chuck would throw us solos on almost every songâŠvery generous in that regard.

A reviewer wrote that to his ears Charles Jr. is playing the lead of "Johnny B. Goode" on the new CD. Did father and son share and distribute the lead guitar solos?

No, thatâs clearly Chuck on Johnny B. Goode here. Chuck did almost all the lead guitar on stage and threw Charles Jr. some solos during the set. Charles Jr. does a solo at approximately 1:57 of Roll Over Beethoven right after mine. Charles Jr.âs rhythm guitar can be heard throughout this CD on the left channel.

Chuck was close to eighty years when these recordings were made. We almost cannot notice when he sings and plays.

You cannot notice in these 2005 shows, but as his later show recordings sadly indicated, Chuckâs hearing was seriously degraded. He had some expensive hearing aids but he didnât like wearing them onstageâŠone actually fell out on the stage and could not be found later!

Bob, what is your favorite recollection from Blueberry Hill?

One of the coolest things I remember about the Blueberry Hill shows was hearing and watching Chuck warm up with his guitar backstage before the show. Chuck would warm up with his guitar while not plugged into an amplifier. It was amazing to hearâŠall the classic Chuck Berry licks played perfectly by the man himselfâŠoften did some amazing things which I never heard him do onstage. It was like all the years and age were stripped away and he was back again playing in the 50âsâŠIâm so sorry that I never asked Chuck whether he would allow me to record him on my iPhoneâŠabsolutely amazing. You could also hear him warming up when he was changing clothes in the bathroom. Once he opened the door and I watched him playing guitar in the mirrorâŠChuck told me he liked playing in the bathroom because the reverb reminded him of the Chess studio!

Many thanks for your explanations, Bob! We appreciate to hear from "the sources".

Saturday, May 7. 2022

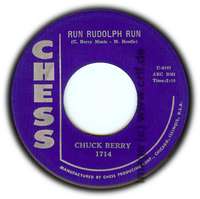

Run! Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer â and the copyright mystery

It's Christmas time and while listening to the radio, from time to time you'll hear one of the various cover versions of Berry's Run Rudolph Run. Berry's???

While everyone will tell you that this is a typical Chuck Berry song with a typical Berry melody (later re-used at the same session for Little Queenie) and typical Berry lyrics (Said Santa to a boy child, "What have you been longing for?" — "All I want for Christmas is a Rock and Roll electric guitar!"), all over the Internet you will read that this song was written by Johnny Marks and Marvin Broadie! And this includes Wikipedia âŠ

With the help of three fellow Berry experts, biographer Bruce Pegg, discographer Morten Reff, and sessionographer Fred Rothwell, I've tried to sort out a few facts from the rumors.

In 1939 Robert L. May wrote the story of Rudolph, the red-nosed reindeer, first for his daughter Barbara, later as a giveaway booklet for his employer, the Montgomery Ward Company. Ward's was the first owner of the Rudolph copyright. In 1946 the copyright was transferred back to May and today belongs to The Rudolph Company, L.P., that means May's heirs.

In 1949 Johnny Marks, husband of May's sister Margaret and both a songwriter and radio producer, took the tale and created the famous Christmas song Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer. The singing cowboy Gene Autry seems to be the first who recorded the song (though some sources name Harry Brannon) and made it a huge hit. Copyright to the 1949 Rudolph song is owned by Marks own publishing company called St. Nicholas Music, Inc.

In 1958, Chuck Berry recorded his version of a Christmas story named Run Rudolph Run. The original Chess release 1714 came with this authors line:

(C. Berry Music — M. Brodie) / ARC BMI

Chuck Berry Music, Inc., Berry's company, is listed here as the author as it is on most Chess singles starting with Beautiful Delilah up to Ramona Say Yes. For some reasons, probably financial, it seems to have made sense to use a company name here instead of an individual's name. As the melody is pure Chuck Berry, it's no wonder that Chuck Berry Music, Inc. claimed authorship and that ARC, the Chess/Goodman publishing company, claimed copyright.

But, mystery #1:

Who is "M. Brodie"? Chuck Berry using a co-writer? A person named M. Brodie does not exist on the Internet. Not as a songwriter nor in any relation to a record company. So if M. Brodie was a songwriter, Run Rudolph Run is his or her only published work. But M. Brodie might also have been someone Berry or the Chess Brothers wanted to give a favor (money/fame) â as they did with Alan Freed on the original Maybellene record. Or M. Brodie might be just a pen name such as "E. Anderson" on Let It Rock who was Berry in disguise.

In the ASCAP authors database, the co-writer of Run Rudolph Run named M. Brodie is identified as member number 268788988. While it's strange that Run Rudolph Run even exists in the ASCAP database because the original single clearly refers to the rival songwriter organization BMI, it becomes even more strange:

Member number 268788988 has additional entries for songs he wrote or co-wrote. All these additional songs stem from albums recorded by a late 1990s group called the Soultans of which a Marvin Lee Broadie was lead singer. And Marvin Lee Broadie indeed wrote some Soultans songs such as Cross My Heart on their Love, Sweat and Tears album. But if you look at Broadie's photo on his concert management site, I strongly doubt he was even born when Berry's Rudolph hit the record stores. Or, as Bruce Pegg puts it:

So unless this songwriter wrote one song in 1958, then had 40 years of writers block only to surface again as a writer for a German pop band at the end of the 90s, this Mr. Broadie is not our man.And don't overlook the different spelling of M. Brodie and Marvin Broadie.

So let's go to mystery #2:

Up to today on all Chess records or re-releases Berry's recording is always credited to Berry/Brodie or just Berry, this includes the latest HIP-O-Select boxes. In contrast, the ASCAP database and almost all cover versions name the songwriters as Johnny Marks and Marvin Broadie. Marvin Broadie aside, what has Johnny Marks to do with the Berry song?

Wikipedia claims that Marks indeed wrote the song, though Wikipedia fails to give a source for this claim. Is it likely that Marks wrote the Berry tune? Not if you compare Run Rudolph Run to Autry's hit record. But if you knew that in 1958 Marks wrote Brenda Lee's Rockin' Around the Christmas Tree, that story might not be too far away. Our mysterious M. Brodie could be an alias for Johnny Marks, which allowed him (an ASCAP songwriter) to team up with Berry (a BMI songwriter). However, while this is possible, I don't believe it.

More likely is a different, more logical link to Marks. His publishing company St. Nicholas Music, Inc. is very strict about copyrights. And in fact the company was created by Marks just because of the Rudolph song and to cash on its success. As such it has "exploited the name and likeness of Rudolph via trademarks in connection with a wide variety of products and services, such as musical performances, audio recordings, sheet music and other music publications" (quoted from court papers). So Marks may have forced Arc Music/Chess Records to register the song with ASCAP and under the Marks/Brodie name. St. Nicholas Music, Inc. along with Character Arts, LLC (which owns the rights to the Rudolph 1964 TV special) successfully forbids Rudolph to appear in movies unless you pay for a license. And they certainly forbid Rudolph to appear in songs as well.

I'm really glad that my rights to the Rudolph name are older than theirs. Otherwise I might have feared their lawyers for using it.

The mysteries remain. I am 100 per cent sure that the mysterious M. Brodie never heard himself called Marvin. This dual use of the 268788988 member number in the ASCAP database is certainly an error introduced by trying to remove variant spellings for the same writer. This is where M. Brodie was mixed up with Marvin Lee Broadie. Johnny Marks' entry to the game was most certainly due to legal reasons. I strongly doubt Marks' contribution to the song, but if you can put some light into this darkness, let me know.

[Addition 31-01-2022:]

Someone sent me a copy of a Facebook post by Daryl Davis, who played piano behind Chuck Berry in later years. Unfortunately I don't have a link or date to share.

Daryl reports on a discussion between him and Berry in preparation for a New Year's Eve show at B.B.King's in NYC:

I asked him about why Run Run Rudolph a/k/a Run Rudolph Run was often credited to Johnny Marks and somebody named Brodie. He said that he wrote the song himself but the name "Rudolph" had been trademarked and the publishing company publishing his songs had been sued for his using it. He was perturbed that the publishing company didn't fight the suit more vigorously, because Johnny Marks had nothing to do with his song and now he had to share the copyright. He also said that Brodie did not exist and it was a scheme to make more money for Marks and his publisher. He regretted not pursing it more at the time. But he still continued to make a lot of money from the song, just not as much as he was entitled to make. It was a bittersweet song for him.

[Addition 07-05-2022:]

In today's news there was some reporting about limitations to fair use of fictional characters in local copyright laws, in this case German Urheberrecht. A very well-known song in Europe is the title song to the 1969 TV series Pippi Longstocking. The original Swedish lyrics were written by Astrid Lindgren herself (melody by Jan Johansson). The German lyrics were written by Wolfgang Franke. 60 years after Lindgren's initial complaints about not getting compensation for use of her fictional character in Franke's text, copyright court rulings and a final settlement between the heirs explained that at least following these local laws you're not free to use the name and properties of a fictional character without sharing the income. Following this, at least here in Germany Robert May was entitled to shared copyright on the Rudolph lyrics.

Saturday, May 1. 2021

Farewell to my favourite RnR magazine

The magazine started in 1977, produced by three Rock'n'Roll fanatics who complained about the lack of reliable information about 1950s music and performers. So Claus-D., H.-GĂŒnther and Wilfried decided to research and publish by themselves.

RRMM was a magazine made by fanatics and made for fanatics. My subscription started with issue number five in 1978.

When I started writing about Chuck Berry, RRMM was the logical choice: an early concert report made it to number 35 in 1983, a two-part biography with discography was published in numbers 49 and 50 in 1986. Since then whenever there was something of interest to tell about Chuck Berry, I was happy to write an article for the German-language readers. My final contribution was in the next-to-last issue published this January.

As everyone interested in 1950 Rock 'n' Roll knows, all of the famous performers have died or at least are becomming very old. And so did the readers of RRMM. In the end, there were so few subscriptions that printing the magazine was no longer reasonable.

I want to thank all the fellow writers at RRMM for doing all the research and for providing all their results to us, especially Dieter and Klaus. And many, many thanks to Waltraut and H.-GĂŒnther for keeping the magazine alive for 44 years!

Those of you who don't know the magazine still have a chance to buy certain back-issues. Look at the list of available issues at http://rocknroll-magazin.de/index/archiv. If you don't read German, don't worry. Translation software such as Deepl is excellent and will easily output a readable English version of everything you don't understand.

Friday, April 16. 2021

The Toronto Concert Complete - not yet - still

The audio was published on hundreds of vinyl and CD albums starting with the 2-LP set Live in Concert (Magnum LP-703) in 1978. The optical recording was used as early as 1970, most importantly in D.A. Pennebaker's movie Keep On Rockin' from 1972.

The interesting thing to collectors is that none of the audio or video releases contains the entire performance. The 2-LP set has, very uncommon for a live recording, each song completely separated with faded start and ending. The movie contains just a selection of songs as well as some in-between talks, but cut and spliced as it fitted to the director.

it is totally unclear why there has never been a complete release of the entire show. At least in the 1980s and 1990s a more complete source still existed, as budget re-releases of the concert contained indeed MORE than the original Magnum album. For instance a French LP album contains half a minute of introduction between School Day and Wee Wee Hours.

Thus at least in the 1990s some company still owned a more complete, maybe entire tape of the show they could license. Some labels used this, though never in total.

It is unclear whether this tape still exists somewhere. When Bear Family in 2014 released their huge Berry box, they tried to find it, but didn't succeed. Therefore Bear Family extracted the only song from the show still missing an audio release (the short Bonsoir Cherie) from Pennebaker's movie.

We all thought this would be the end of the story. But a few days ago, Sunset Blvd. Records released another audio CD with music from Toronto, but promoted their release with a prominently placed large sticker:

Even those like me who already have dozens of records containing the same show, felt tempted to buy one of the (pretty expensive) CDs. Don't do it!

Also Sunset Blvd. Records (SBR) did NOT find the original audio tape. Instead they cut and spliced available and well-known material trying to recreate the original concert. There's nothing wrong trying so. I did the same in 1997. However, I used all the material from all the sources. SBR obviously only had the Magnum album and Pennebaker's film.

This means that several of the transitions between songs are missing from this CD. And it means that what sounds like on-stage chatter and comments is not at the correct place, since Pennebaker already had cut and spliced segments from all over the concert and shuffled them around.

The songs are not in the correct sequence and parts of the show are omitted even though already known. The only interesting thing is that SBR included Kim Fowley's introduction to Berry.

So this is a fake! And at some time SBR must have recognized it. MC Kim Fowley is heard twice at song endings applauding Berry. One is at the non-medley version of Johnny B. Goode and thus also on the SBR CD. A second time is at the end of Maybellene.This and its placement at the end of the Magnum 2-LP set lets me assume that this song is one of the rare encores in a Berry concert. SBR instead decided to place Maybellene after I'm Your Hoochie Coochie Man which ends with Berry asking "You name it, we play it." Maybellene starts with "Did I hear Maybellene?" Fits, thought the people at SBR. But this required them to cut off Kim Fowley from the end of the song and to fade over into Too Much Monkey Business.

And indeed it's too much monkey business here. Why to spend all the effort to create such a fake? Either you have the original tape or you don't. But don't pretend to have it.

Interestingly the liner notes refer to and correctly name our database as a source. So they must have found this site. But why didn't they read the long chapter we have dedicated to this concert alone? All this leaves us fairly disappointed.

To end with a positive note: Have a look at Don Pennebaker's description about how the title Keep On Rockin' got selected and about his visit to John Lennon's bedroom showing him the film: https://phfilms.com/films/sweet-toronto-keep-on-rockin/#summary

Somehow Pennebaker misses to tell that Lennon demanded payment for his appearance and thus had to be cut from the film.

Monday, April 12. 2021

Jon Brewer's official Berry documentary - now on DVD

As a reminder: The film is a typical documentary/interview combination. The documentary part is taken from very well known sources, mostly from Taylor Hackford's "Hail! Hail! Rock 'N' Roll" and its DVD bonuses. New interview segments are from many known musicians such as Johnny Rivers, Gene Simmons, Steve Van Zandt, George Thorogood, and Alice Cooper. The most interesting segments are interviews with the Berry family and close friends which speak quite frankly (though of course biased) about living and working with Chuck. So we listen to Chuck's wife Themetta, their children Charles, Ingrid, and Melody, the grandsons Charlie and Jahi as well as Jim Marsala, Joe Edwards, and Wayne Schoenberg. In total it is a very complete and historically exact description of Berry's life and career. And if you exclude Elise LeGrow, the soundtrack is perfect.

The DVD contains both the 103-minute documentary as well as larger segments of the interviews used within the film. This way you get another 100 minutes of talks about Chuck Berry by musicians Alice Cooper, Gene Simmons, Steve Van Zandt, George Thorogood, Joe Perry, Nils Lofgren, Nile Rodgers, Joe Bonamassa, and Johnny Rivers as well as by family and friends Ingrid Berry, Charles Berry Jr., and Jimmy Marsala. Recommended.

The DVD unfortunately is Region-coded. It will only play if your DVD player is able to show Code 1 DVDs (US+Canada). If it does you can buy it from the usual online stores even outside the U.S.A.

Wednesday, February 19. 2020

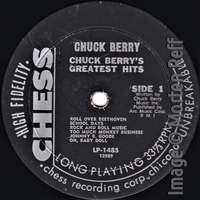

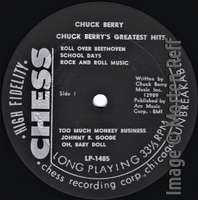

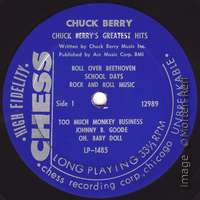

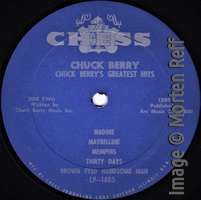

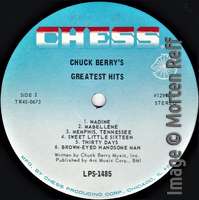

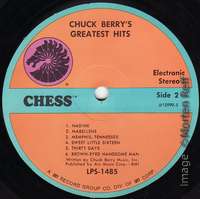

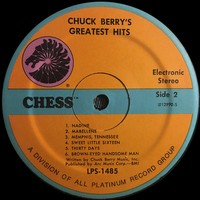

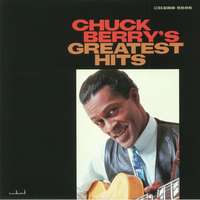

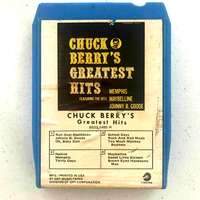

Chuck Berry's Greatest Hits (Chess LP-1485)

CBID is the Chuck Berry International Directory, a 2.200 page pile of Chuck Berry records information published in four volumes between 2008 and 2013. For details see the bibliography section of this site.

CBID is never complete as new records and CDs appear and some old rarities are discovered. This section presents interesting additions and corrections to CBID.

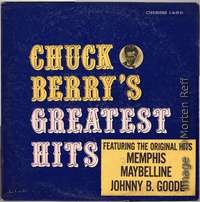

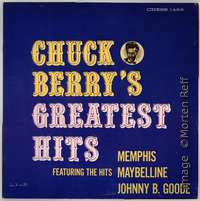

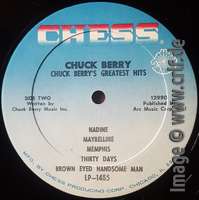

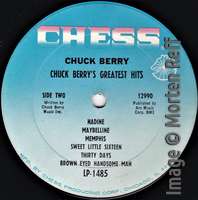

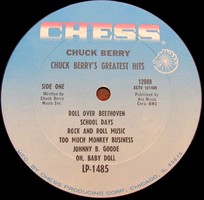

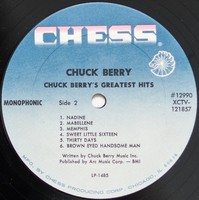

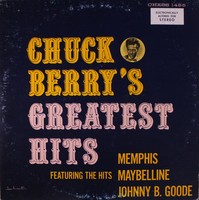

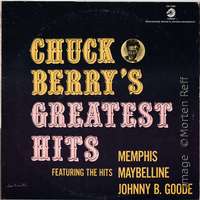

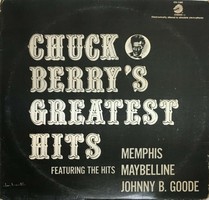

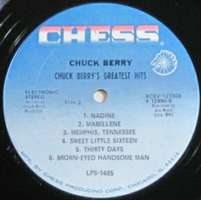

Today: After we have seen that there were three different versions of the cover of Chess LP-1480 Chuck Berry On Stage it is time to explain that the same variants (initial print, sticker, and final print) can also be found with Chess LP-1485 Chuck Berry's Greatest Hits. And while we're at it, we also have a deeper look at the multiple labels found with this album.

USA

CHUCK BERRY'S GREATEST HITS

Chess LP-1485 • April 1964 + reissues

This is another of those Berry LPs that has come out with countless number of label variants and three different front covers, six if you count the el.stereo ones numbered LPS-1485. Itâs been reissued so many times, Morten has 8 different copies of this album, cover and label, and we have been made aware that even more variants exist through readers of this site. This text should help collectors to understand the various releases of a record published for more than a decade using the same catalog number and a basically unchanged cover.

- The first cover didnât have any titles listed on the blue front side.

- Just like with the On Stage album (Chess LP-1480) soon thereafter the cover received a sticker containing important song titles printed in black on yellow: Memphis, Maybellene, and Johnny B. Goode. (Memphis had been a hit by both Lonnie Mack and Johnny Rivers (1963-1964), Maybellene a hit by Johnny Rivers (1964), and Johnny B. was a classic everybody was doing.). Note aside: this was the first occasion that âMaybelleneâ was incorrectly spelt with an âiâ.

- Finally the most common variant of the cover contains the same titles printed in yellow in the bottom right-hand corner (see images). And take notice of the different spelling, Featuring the original hits on the sticker, contra the later printed version Featuring the hits.

Here are the three covers of Chess LP-1485. As with all images on this site you can enlarge them by clicking.

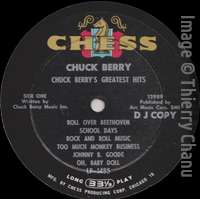

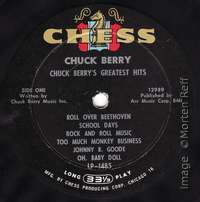

Again as with the On Stage album, the first records sent out to disk jockeys at radio stations were produced using the then new (and expensive) multi-color label with the golden Chessknight logo (sometimes referred to as the 'crest' logo). Our good friend and expert on US album releases, Thierry Chanu, whom we unfortunately lost a few weeks ago (bless his soul), provided this image of a DJ Copy label:

The same label template and print was also used for commercial records, though less the DJ COPY print:

When reading about LP-1485, records with the multi-color label are often called a second or later pressing. This does not make sense if the initial very first records produced, the DJ copies, already had this label. Such saying stems from a misunderstanding about how the recording industry worked during the mid-Sixties.